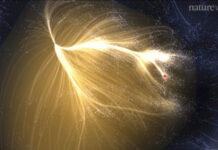

An international team of astronomers has discovered that most of the iron in intergalactic gas formed long before galaxies assembled into clusters. This finding indicates that the first galaxies must have been very violent environments with powerful supernovae producing heavy elements and supermassive black holes pushing this new material between galaxies.

The study, accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, confirms previous findings suggesting that most of the iron in the universe was produced in the first 3 billion years.

“If these elements were produced relatively recently, astronomically speaking, then we would expect a different concentration of iron from cluster to cluster,” lead author Ondrej Urban, who was a PhD student at Stanford University when he performed the extensive data analysis of this research, said in a statement. “The fact that the distribution of iron appears so homogeneous, indicates that it has been produced by some of the first stars and galaxies that formed after the big bang.”

The Big Bang formed everything we see today but not exactly in its current form. A lot of hydrogen, some helium and a dash of lithium were formed at the beginning and everything else was created by stars through nuclear fusion in their cores.

The first stars, which we are yet to observe, are believed to be much bigger than current stellar objects. Estimates suggest that they could be up to 1,000 times heavier than our Sun. Such gargantuan mass meant a short lifetime, ending in incredible explosions. These supernovae began spreading heavier elements around galaxies, but only when supermassive black holes started producing powerful jets did this material began to spread in intergalactic space.

“The remarkably uniform distribution of iron also means that the combined energy of many supernovae and the jets and winds of accreting supermassive black holes were able to mix the elements thoroughly across the Universe,” added the corresponding author of the study, Norbert Werner, leader of the “Lendület Hot Universe” research group at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest. Werner will present their findings this week at the annual meeting of the European Astronomical Society, EWASS2017, in Prague, Czech Republic.

The observations they made were possible thanks to the sophisticated Suzaku satellite, a precise X-ray observatory. It was an American-Japanese collaboration and it was switched off in 2015, due to technical issues after 10 years in service.